A 1000 year-old Elm Tree Root?

the mael of Malden?

Evidence on this Signboard on Church Path, where you can see an elm tree growing out of a tomb is updated on this website as information comes in.

Standing in front of this board, you are on a hill (a ‘dune’ in Anglo-Saxon). Once it was marked by a Saxon sign (a mael). Malden was maeldune - ‘Sign Hill’. The original mael was a sign on this path, a way-marker on a highway, a dry way, the safe, direct way to civilisation. For Saxons, this was not just a blip on the London Loop.

Before any church was here, Christian faith was probably taught under this mael. Deals were struck here, more sure they would be faithfully kept. Like many way-signs, the mael probably became the village cross, the sign of Christ, christes mael. The church built close to it, bore witness to the sign. Malden itself was named after this sign.

The only material for a sign here was wood. Malden had no masonry stone. Elm trees were the tall, natural landmarks. They could grow 40 metres high. Some lasted hundreds of years, standing tall above the woodland.

On the south side of Church Road elm trees as tall as the lamp standards are crowding the roadside now.

Sadly, because of elm disease, all of them will probably die back no more than 12 metres high.

Under wet ground, however, or surrounded by living bark, elm wood is extraordinarily durable.

This piece of water pipe, made from elm wood is now in the Science Museum, dated 1401-1600.

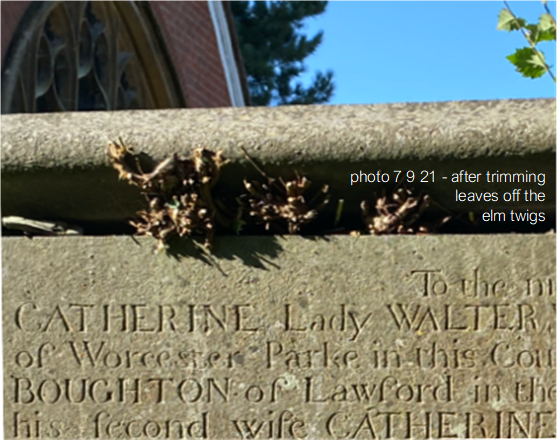

But in the churchyard not one elm could be found - except those invading at the boundary. But, about ten years ago, an elm tree began growing out of the top of Catherine Lady Walter’s family memorial.

Branches of elm have forced up the stone slab on top of this monument - although it weighs about a ton. Elm root suckers must have broken through layers of masonry in the vault underneath, then climbed inside the memorial and the vault beneath it. But the roots must have remained dormant in the clay under the vault for at least 270 years.

Though every leaf of it had been removed the previous winter, this tree of elm, three metres tall, had grown out from under the slab, before April 2020.

Elm wood is hard to remove. It is tougher than oak. A single shred of elm root very soon becomes a whole elm tree. But Lady Walter’s vault and the deep clay mound around it, seem to have successfully smothered the elm roots for nearly three centuries. There must have been years of conscientious mowing, scything and probably grazing by farm animals and deer as well.

Lady Walter of ‘Worcester Parke’ had died in 1733. Her memorial was to go in front of the church’s east window. But it was placed south of centre. Roots like this, so near to a church, able to produce elm trunks 40 metres high and two metres in diameter, had to be taken very seriously.

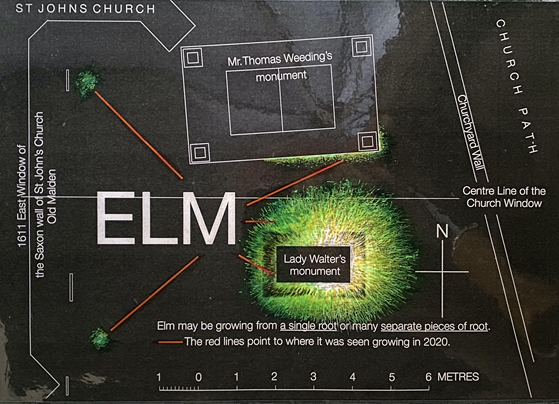

This is Mr.Thomas Weeding’s memorial. When he died, in 1856, it was sited well to the north of centre. The clay mound over his vault was stretched out over Lady Walter’s, perhaps to smother the elm in the central area even more deeply in clay. Portland cement now made concrete foundations much stronger. No elm tree is growing out of the top of his memorial - yet.

But at the corner of the Weeding memorial nearest to the camera, this one tiny elm, at the end of an ‘avenue’ of tiny elms, three metres long, survived the routine grass maintenance in 2021.

But at the corner of the Weeding memorial nearest to the camera, this one tiny elm, at the end of an ‘avenue’ of tiny elms, three metres long, survived the routine grass maintenance in 2021.

It was cut down, but it re-grew. It survived a second strim in September and then a third one in October.

Not all trees cut at ground level die. Elms can grow vigorously as a result. This is the principle used in ‘coppicing’- a successful method used for managing woodland since prehistoric times.

Ash trees, for instance, normally live for 200 years. But they can re-grow for a thousand years if coppiced. Could our elm tree’s life have been prolonged by indefatigable cutting - all those centuries from Saxon times?

How big a root system is still alive?

The drawing below shows the total area where tiny elm ‘saplings’ were found growing in autumn 2021. It is 9 metres long (east to west), and 5 wide (south to north). The roots may have come from a single trunk, but possibly from several. One trunk might die back after 3-400 years but others could develop from the root suckers. Those with the best chance would probably be farthest from the shadow of the old tree and the church building. So, every 3-400 years the tree might appear to ‘walk’ a few paces - out into more open sunlight.

Long stems of elm must have been growing for years, un-noticed, concealed among the brambles and shrubs on all four sides of Lady Catherine’s memorial, growing out of the ceiling of the vault, underneath the monument.

When, in 2021, a shallow trench was dug round the church to reduce damp, a 3mm thick elm root under the east window in the Saxon wall was severed and exposed. This root was heading due west from Lady Catherine’s tomb towards the foundations of the church. It must have detected more moisture and/or nutriment there than in the open grass.

A few months later, that root had sprouted a 20cm tall elm sapling with fresh young leaves. Trimmed with the grass in late October, smaller, darker elm leaves were uncovered. They had been hidden in the grass, completely unnoticed.

What action should be taken?

There are good reasons to conserve both tree and monument. Kingston ecologist, Alison Fure, suggests elm can be managed as a hedge. Could new branches in a hedge perhaps be trained to protect and support the monument rather than breaking it apart? If the elm disease kills branches, can this root still send up healthy ones? Could branches perhaps be trained so everyone could see and be part of the breaking story, proud of the elm, the mael and the monument? Once, perhaps, this elm was an awe-inspiring forty-metre-high landmark, fashioned by Saxon craftsmen into a cross. A sign gave Malden its name. Perhaps this sign gave this place a new direction for a thousand years. .

What must we do to discover if this elm was definitely the ancient sign on this hill? Are there better ways to conserve the monument and to value this ancient tree?

Please send suggestions to: conservation@stjohnsoldmalden.org.uk

footnotes to the Signboard on Church Path

adapted from Old Malden News September 2021 (Footnotes to a notice board on church path)

‘St John’s should have a notice board outside it telling the story of conservation there’. Barbara Webb told me that again, the very last time we met. Botanical evidence has appeared about this sign that gave Malden its name. If she had been here to see an elm tree growing out of the top of Lady Walter’s monument as we did this year, she might have relished the job of weaving it into the wonderful talks she gave on her Heritage Week walks. How we would value her views now about conserving both the monument and the elm tree that seems to be destroying it.

This elm theory was given a test-drive on the Heritage Days. Valuable advice came in from Kingston ecologist, Alison Fure. She reminded me, Barbara fashion, what matters is to cut and clear the grass properly, rather than “micro-manage” projects (like this?). She told me elm is now being grown successfully from seed. But this Signboard forms a key step from last year’s board featuring the Spring underneath St John’s Church. So much information is coming from this elm discovery, that it is being made available now to read in comfort at home by using a QR code on the Signboard.

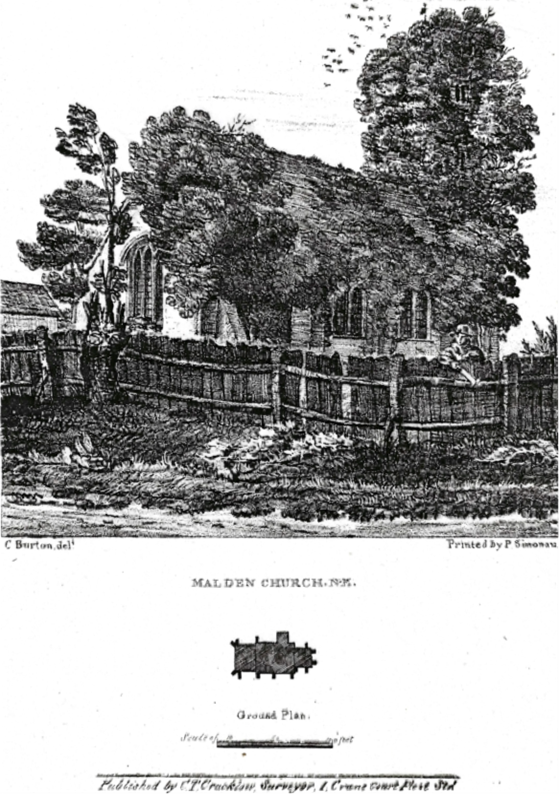

In spite of much evidence of elm roots still underneath the grass, none of the old engravings of the church, starting in 1799, showed any sign of a tree near the church’s east window. The prints probably just told us how successfully elm trees can be kept out of sight by very conscientious lawn-mowing.

In Heritage week, however, this lithograph of St John’s was re-discovered. It is thought to have been drawn about 1825. It shows a tree stump outside a very rough wooden church fence. The stump is about 70 cm wide, judging by the height of the man. He is posed, displaying a bill-hook, the tool used to cut brushwood and narrow branches. Several branches growing out of the stump have already been chopped short. On the grass verge outside the fence, debris may be piled ready for carting away. The artist’s view-point places the stump in front the east window.

The man has nearly completed his work, deliberately leaving one 5 metre high branch growing out of the top of the stump (to show how much there was to remove?). The stump will soon be smartly pollarded again, allowing unobstructed views of the church.

Workmen today take photos on their phones to prove when they turned up at a job, and completed it. Maybe Mr. C. T. Cracklow, a surveyor (named at the bottom of the print) commissioned this lithograph, using the very latest copying method to keep an eye on his employees? He got C. Burton to sketch a ‘snapshot’. P. Simonau then printed enough lithographic copies to satisfy the P.C.C., the Vicar, Merton College, whoever is paying to have the stump sorted out.

Surplus prints from his surveillance exercise amused print collectors, who bought them as a quaint village scene, showcasing the latest Paris print technology. (Amazingly, copies can still be bought on the net today!)

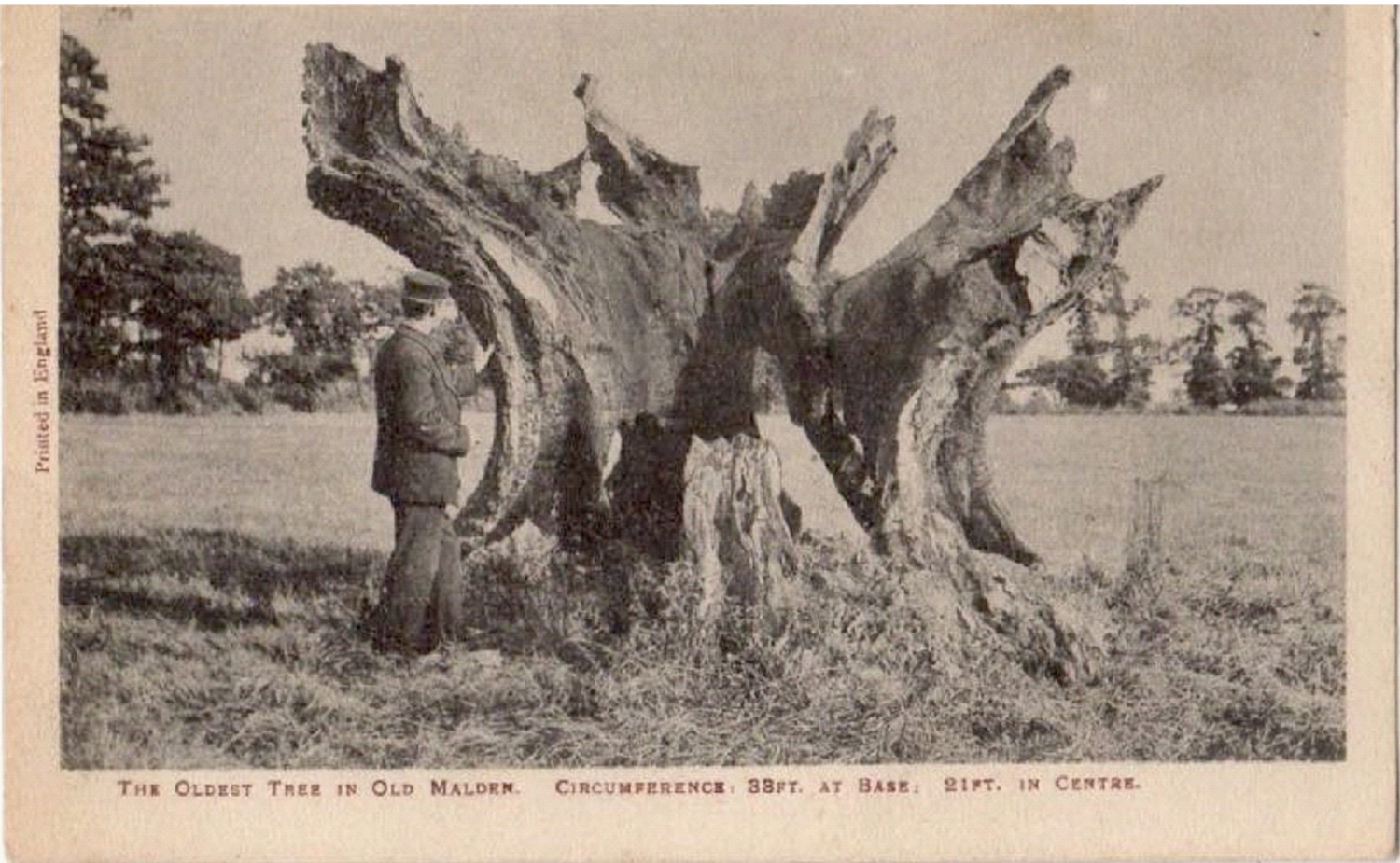

Robin Gill kindly sent us this postcard issued in the 1900s showing “The Oldest tree in Old Malden”. It is in a large, level, well-cut field. Five clearly distinguishable English elms mark its boundary at the horizon on the right. So it is likely to be an elm. Can you tell us where this field is, or was? Are those elms or their stumps now at the end of someone’s garden or in colour prints on your family photos?

The largest known English Elm in Europe was in the news recently, being removed on a lorry because it had Dutch elm disease. Also hollow, also with a trunk two metres in diameter, it dated back 400 years. This news confirmed that before elm disease, elms might stand for that length of time, but would then tend to become too frail. This tree was one of two ‘twin’ trees in Preston Park, Brighton.

The dedicated folk who kept these alive may be the ones to ask whether ancient elms produce root suckers which ultimately take the place of the tree. Someone studying peat bogs may be able to tell us if there are ring patterns in roots preserved under wet ground that show the dates of fragments of root preserved there. Only four cycles of 300 hundred year old trees would take our tree back 1200 years and to Saxon times. How many elm fence posts would the tree have supplied in that time if it had been coppiced? And if all the trunks and branches originate from a single root mass, could our Malden Elm growing out of Lady Walter’s memorial be proved to be a living part of the original Saxon mael?

Could be an excuse for a trip to a park in Brighton, but the wonders of the web may bring the story to all of us without even leaving our screens.